I needed a bit of a break from “real work” recently, so I started a new programming project that was low-stakes and purely recreational. On April 21st, I set out to see how much of a Unix-like operating system for x86_64 targets that I could put together in about a month. The result is Bunnix. Not including days I didn’t work on Bunnix for one reason or another, I spent 27 days on this project.

You can try it for yourself if you like:

To boot this ISO with qemu:

qemu-system-x86_64 -cdrom bunnix.iso -display sdl -serial stdio

You can also write the iso to a USB stick and boot it on real hardware. It will probably work on most AMD64 machines – I have tested it on a ThinkPad X220 and a Starlabs Starbook Mk IV. Legacy boot and EFI are both supported. There are some limitations to keep in mind, in particular that there is no USB support, so a PS/2 keyboard (or PS/2 emulation via the BIOS) is required. Most laptops rig up the keyboard via PS/2, and YMMV with USB keyboards via PS/2 emulation.

Tip: the DOOM keybindings are weird. WASD to move, right shift to shoot, and space to open doors. Exiting the game doesn’t work so just reboot when you’re done playing. I confess I didn’t spend much time on that port.

What’s there?

The Bunnix kernel is (mostly) written in Hare, plus some C components, namely lwext4 for ext4 filesystem support and libvterm for the kernel video terminal.

The kernel supports the following drivers:

- PCI (legacy)

- AHCI block devices

- GPT and MBR partition tables

- PS/2 keyboards

- Platform serial ports

- CMOS clocks

- Framebuffers (configured by the bootloaders)

- ext4 and memfs filesystems

There are numerous supported kernel features as well:

- A virtual filesystem

- A /dev populated with block devices, null, zero, and full psuedo-devices, /dev/kbd and /dev/fb0, serial and video TTYs, and the /dev/tty controlling terminal.

- Reasonably complete terminal emulator and somewhat passable termios support

- Some 40 syscalls, including for example clock_gettime, poll, openat et al, fork, exec, pipe, dup, dup2, ioctl, etc

Bunnix is a single-user system and does not currently attempt to enforce Unix file modes and ownership, though it could be made multi-user relatively easily with a few more days of work.

Included are two bootloaders, one for legacy boot which is multiboot-compatible and written in Hare, and another for EFI which is written in C. Both of them load the kernel as an ELF file plus an initramfs, if required. The EFI bootloader includes zlib to decompress the initramfs; multiboot-compatible bootloaders handle this decompression for us.

The userspace is largely assembled from third-party sources. The following third-party software is included:

- Colossal Cave Adventure (advent)

- dash (/bin/sh)

- Doom

- gzip

- less (pager)

- lok (/bin/awk)

- lolcat

- mandoc (man pages)

- sbase (core utils)1

- tcc (C compiler)

- Vim 5.7

The libc is derived from musl libc and contains numerous modifications to suit Bunnix’s needs. The curses library is based on netbsd-curses.

The system works but it’s pretty buggy and some parts of it are quite slapdash: your milage will vary. Be prepared for it to crash!

How Bunnix came together

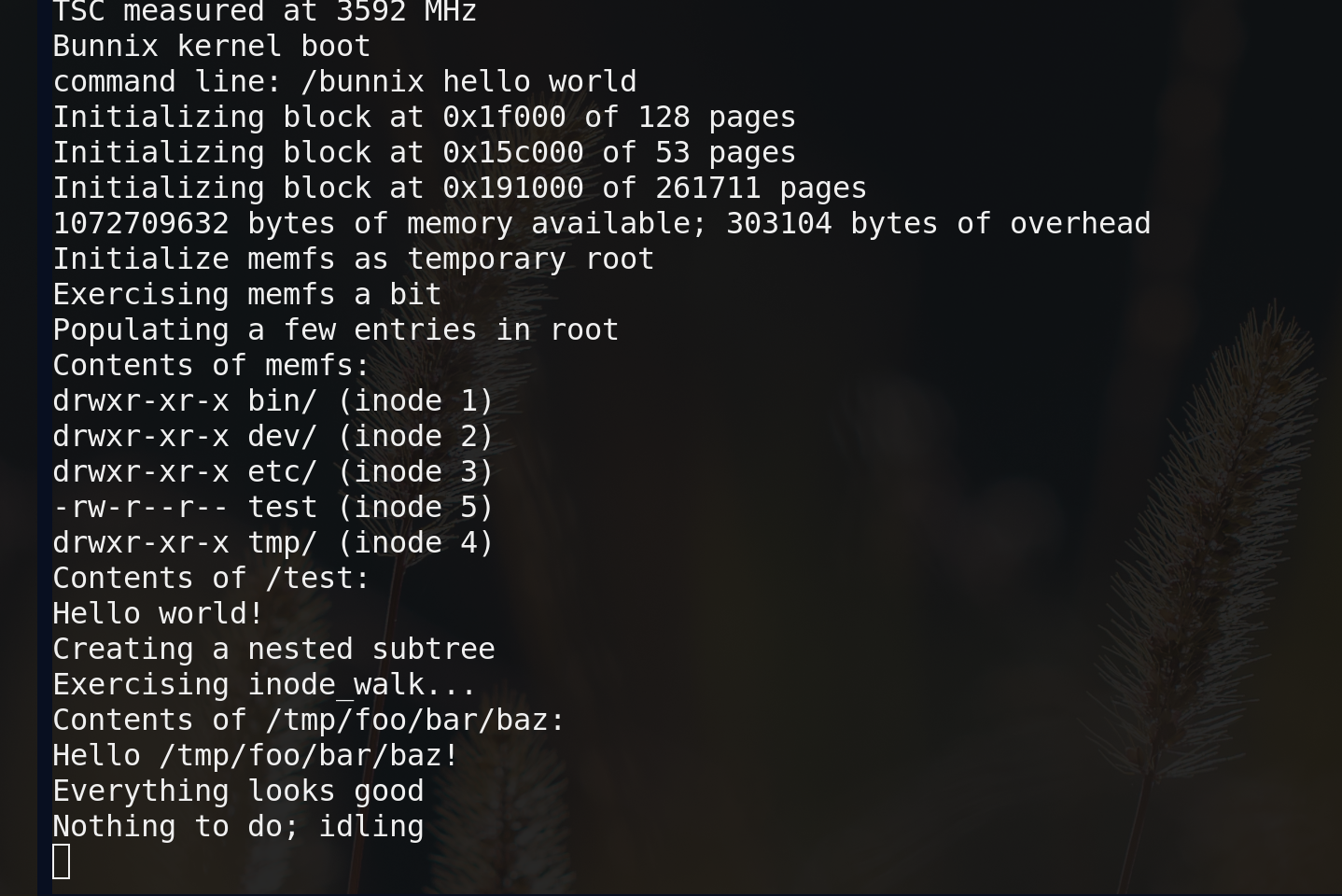

I started documenting the process on Mastodon on day 3 – check out the Mastodon thread for the full story. Here’s what it looked like on day 3:

Here’s some thoughts after the fact.

Some of Bunnix’s code stems from an earlier project, Helios. This includes portions of the kernel which are responsible for some relatively generic CPU setup (GDT, IDT, etc), and some drivers like AHCI were adapted for the Bunnix system. I admit that it would probably not have been possible to build Bunnix so quickly without prior experience through Helios.

Two of the more challenging aspects were ext4 support and the virtual terminal, for which I brought in two external dependencies, lwext4 and libvterm. Both proved to be challenging integrations. I had to rewrite my filesystem layer a few times, and it’s still buggy today, but getting a proper Unix filesystem design (including openat and good handling of inodes) requires digging into lwext4 internals a bit more than I’d have liked. I also learned a lot about mixing source languages into a Hare project, since the kernel links together Hare, assembly, and C sources – it works remarkably well but there are some pain points I noticed, particularly with respect to building the ABI integration riggings. It’d be nice to automate conversion of C headers into Hare forward declaration modules. Some of this work already exists in hare-c, but has a ways to go. If I were to start again, I would probably be more careful in my design of the filesystem layer.

Getting the terminal right was difficult as well. I wasn’t sure that I was going to add one at all, but I eventually decided that I wanted to port vim and that was that. libvterm is a great terminal state machine library, but it’s poorly documented and required a lot of fine-tuning to integrate just right. I also ended up spending a lot of time on performance to make sure that the terminal worked smoothly.

Another difficult part to get right was the scheduler. Helios has a simpler scheduler than Bunnix, and while I initially based the Bunnix scheduler on Helios I had to throw out and rewrite quite a lot of it. Both Helios and Bunnix are single-CPU systems, but unlike Helios, Bunnix allows context switching within the kernel – in fact, even preemptive task switching enters and exits via the kernel. This necessitates multiple kernel stacks and a different approach to task switching. However, the advantages are numerous, one of which being that implementing blocking operations like disk reads and pipe(2) are much simpler with wait queues. With a robust enough scheduler, the rest of the kernel and its drivers come together pretty easily.

Another source of frustration was signals, of course. Helios does not attempt to be a Unix and gets away without these, but to build a Unix, I needed to implement signals, big messy hack though they may be. The signal implementation which ended up in Bunnix is pretty bare-bones: I mostly made sure that SIGCHLD worked correctly so that I could port dash.

Porting third-party software was relatively easy thanks to basing my libc on musl libc. I imported large swaths of musl into my own libc and adapted it to run on Bunnix, which gave me a pretty comprehensive and reliable C library pretty fast. With this in place, porting third-party software was a breeze, and most of the software that’s included was built with minimal patching.

What I learned

Bunnix was an interesting project to work on. My other project, Helios, is a microkernel design that’s Not Unix, while Bunnix is a monolithic kernel that is much, much closer to Unix.

One thing I was surprised to learn a lot about is filesystems. Helios, as a microkernel, spreads the filesystem implementation across many drivers running in many separate processes. This works well enough, but one thing I discovered is that it’s quite important to have caching in the filesystem layer, even if only to track living objects. When I revisit Helios, I will have a lot of work to do refactoring (or even rewriting) the filesystem code to this end.

The approach to drivers is also, naturally, much simpler in a monolithic kernel design, though I’m not entirely pleased with all of the stuff I heaped into ring 0. There might be room for an improved Helios scheduler design that incorporates some of the desirable control flow elements from the monolithic design into a microkernel system.

I also finally learned how signals work from top to bottom, and boy is it ugly. I’ve always felt that this was one of the weakest points in the design of Unix and this project did nothing to disabuse me of that notion.

I had also tried to avoid using a bitmap allocator in Helios, and generally memory management in Helios is a bit fussy altogether – one of the biggest pain points with the system right now. However, Bunnix uses a simple bitmap allocator for all conventional pages on the system and I found that it works really, really well and does not have nearly as much overhead as I had feared it would. I will almost certainly take those lessons back to Helios.

Finally, I’m quite sure that putting together Bunnix in just 30 days is a feat which would not have been possible with a microkernel design. At the end of the day, monolithic kernels are just much simpler to implement. The advantages of a microkernel design are compelling, however – perhaps a better answer lies in a hybrid kernel.

What’s next

Bunnix was (note the past tense) a project that I wrote for the purpose of recreational programming, so it’s purpose is to be fun to work on. And I’ve had my fun! At this point I don’t feel the need to invest more time and energy into it, though it would definitely benefit from some. In the future I may spend a few days on it here and there, and I would be happy to integrate improvements from the community – send patches to my public inbox. But for the most part it is an art project which is now more-or-less complete.

My next steps in OS development will be a return to Helios with a lot of lessons learned and some major redesigns in the pipeline. But I still think that Bunnix is a fun and interesting OS in its own right, in no small part due to its demonstration of Hare as a great language for kernel hacking. Some of the priorities for improvements include:

- A directory cache for the filesystem and better caching generally

- Ironing out ext4 bugs

- procfs and top

- mmaping files

- More signals (e.g. SIGSEGV)

- Multi-user support

- NVMe block devices

- IDE block devices

- ATAPI and ISO 9660 support

- Intel HD audio support

- Network stack

- Hare toolchain in the base system

- Self hosting

Whether or not it’s me or one of you readers who will work on these first remains to be seen.

In any case, have fun playing with Bunnix!

-

sbase is good software written by questionable people. I do not endorse suckless. ↩︎