In many fields, professional-grade tooling requires a high degree of knowledge and training to use properly, usually more than is available to the amateur. The typical mechanic’s tool chest makes my (rather well-stocked, in my opinion) tool bag look quite silly. A racecar driver is using a vehicle which is much more complex than, say, the soccer mom’s mini-van. Professional-grade tools are, necessarily, more complex and require skill to use.

There are two attributes to consider when classifying these tools: utility and usability. These are not the same thing. Some tools have both high utility and high usability, such as a pencil. Some are highly usable, but of low utility, such as a child’s tricycle. Tools of both low-utility and low-usability are uncommon, but I’m sure you can think of a few examples from your own experiences :)

When designing tools, it is important to consider both of these attributes, and it helps to keep the intended audience in mind. I think that many programmers today are overly concerned with usability, and insufficiently concerned with utility. Some programmers (although this sort prefers “developer”) go so far as to fetishize usability at the expense of utility.

In some cases, sacrificing utility in favor of usability is an acceptable trade-off. In the earlier example’s case, it’s unlikely that anyone would argue that the soccer mom should be loading the tots into an F1 racecar. However, it’s equally absurd to suppose that the F1 driver should bring a mini-van to the race track. In the realm of programming, this metaphor speaks most strongly to me in the design of programming tools.

I argue that most programmers are professionals who are going to invest several years into learning the craft. This is the audience for whom I design my tools. What trouble is it to spend an extra hour learning a somewhat less intuitive code review tool when the programming language whose code you’re reviewing required months to learn and years to master?

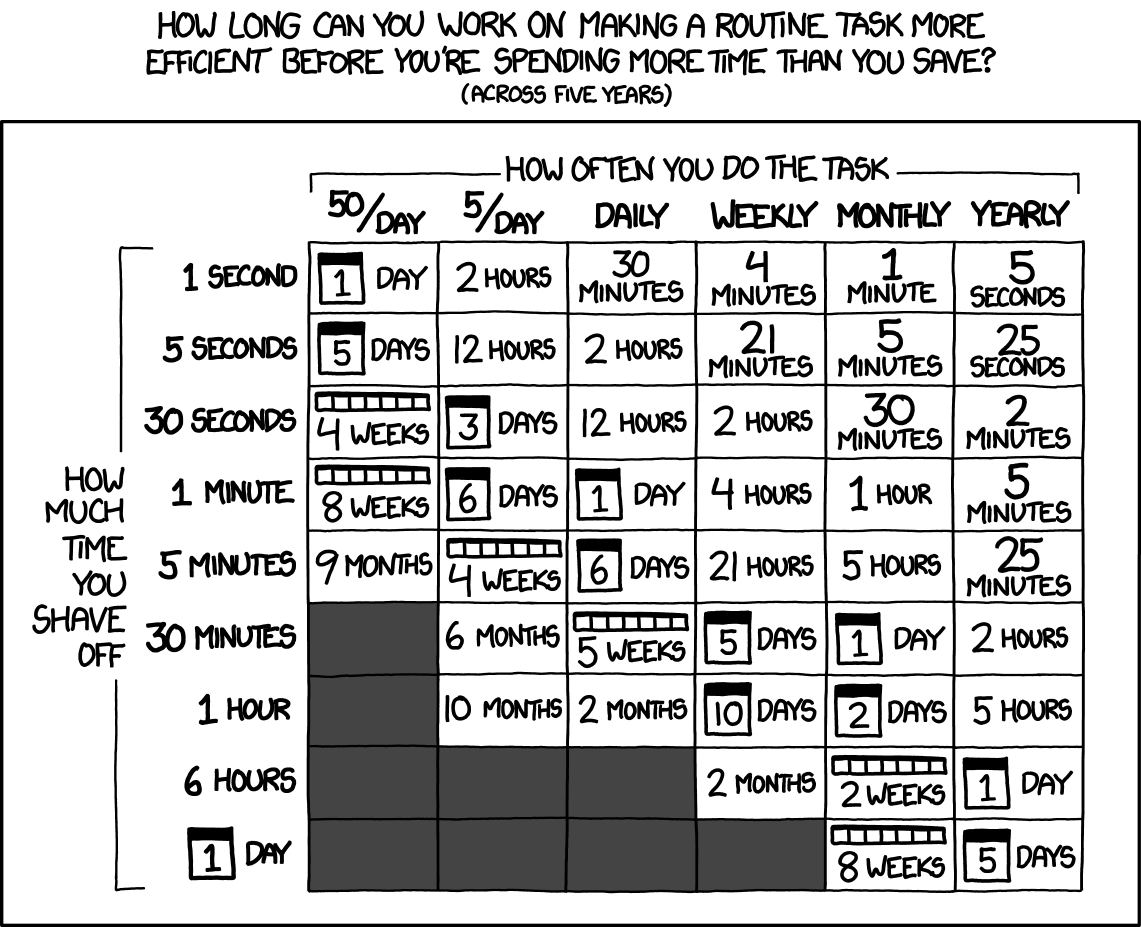

I write tools to maximize the productivity of professional programmers. Ideally, we can achieve both usability and utility, and often we do just that. But, sometimes, these tools require a steeper learning curve. If they are more useful in spite of that, they will usually save heaps of time in the long run.

Instead of focusing on dumbing down our tools, maximizing usability at the expense of utility, we should focus on making powerful tools and fostering a culture of mentorship. Senior engineers should be helping their juniors learn and grow to embrace and build a new generation of more and more productive tooling, considering usability all the while but never at the expense of utility.

I’ll address mentorship in more detail in future posts. For now, I’ll just state that mentorship is the praxis of my tooling philosophy. We can build better, more powerful, and more productive tools, even if they require a steeper learning curve, so long as we’re prepared to teach people how to use them, and they’re prepared to learn.