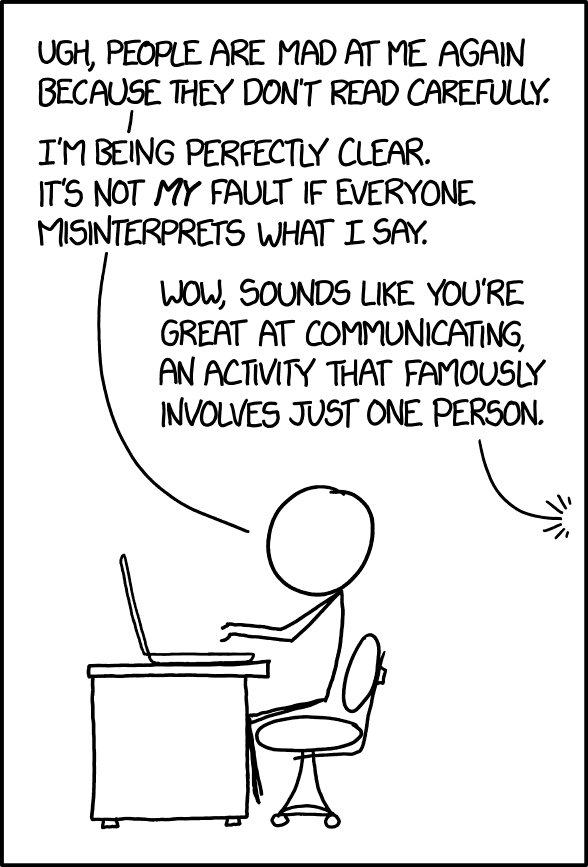

This is a follow-up to my last article, Hello world, which is easily the most negatively received article I’ve written — a remarkable feat for someone who’s written as much flame bait as me. Naturally, the fault lies with the readers.

All jokes aside, I’ll try to state my point better. The “Hello world” article was a lot of work to put together — frustrating work — by the time I had finished collecting numbers, I was exhausted and didn’t pay much mind to putting context to them. This left a lot of it open to interpretation, and a lot of those interpretations didn’t give the benefit of the doubt.

First, it’s worth clarifying that the assembly program I gave is a hypothetical, idealized hello world program, and in practice not even the assembly program is safe from bloat. After it’s wrapped up in an ELF, even after stripping, the binary bloats up to 157× the size of the actual machine code. I had hoped this would be more intuitively clear, but the take-away is that the ideal program is a pipe dream, not a standard to which the others are held. As the infinite frictionless plane in vacuum is to physics, that assembly program is to compilers.

I also made the mistake of including the runtime in the table. What I wanted you to notice about the timestamp is that it rounds to zero for 15 of the 21 test cases, and arguably only one or two approach the realm of human perception. It’s meant to lend balance to the point I’m making with the number of syscalls: despite the complexity on display, the user generally can’t even tell. The other problem with including the runtimes is that it makes it look like a benchmark, which it’s not (you’ll notice that if you grep for “benchmark”, you will find no results).

Another improvement would have been to group rows of the table by orders of magnitude (in terms of number of syscalls), and maybe separate the outliers in each group. There is little difference between many of the languages in the middle of the table, but when one of them is your favorite language, “stacking it up” against its competitors like this is a good way to get the reader’s blood pumping and bait some flames. If your language appears to be represented unfavorably on this chart, you’re likely to point out the questionable methodology, golf your way to a more generous sample code, etc; things I could have done myself were I trying to make a benchmark rather than a point about complexity.

And hidden therein is my actual point: complexity. There has long been a trend in computing of endlessly piling on the abstractions, with no regard for the consequences. The web is an ever growing mess of complexity, with larger and larger blobs of inscrutable JavaScript being shoved down pipes with no regard for the pipe’s size or the bridge toll charged by the end-user’s telecom. Electron apps are so far removed from hardware that their jarring non-native UIs can take seconds to respond and eat up the better part of your RAM to merely show a text editor or chat application.

The PC in front of me is literally five thousand times faster than the graphing calculator in my closet - but the latter can boot to a useful system in a fraction of a millisecond, while my PC takes almost a minute. Productivity per CPU cycle per Watt is the lowest it’s been in decades, and is orders of magnitude (plural) beneath its potential. So far as most end-users are concerned, computers haven’t improved in meaningful ways in the past 10 years, and in many respects have become worse. The cause is well-known: programmers have spent the entire lifetime of our field recklessly piling abstraction on top of abstraction on top of abstraction. We’re more concerned with shoving more spyware at the problem than we are with optimization, outside of a small number of high-value problems like video decoding.1 Programs have grown fat and reckless in scope, and it affects literally everything, even down to the last bastion of low-level programming: C.

I use syscalls as an approximation of this complexity. Even for one of the simplest possible programs, there is a huge amount of abstraction and complexity that comes with many approaches to its implementation. If I just print “hello world” in Python, users are going to bring along almost a million lines of code to run it, the fraction of which isn’t dead code is basically a rounding error. This isn’t always a bad thing, but it often is and no one is thinking about it.

That’s the true message I wanted you to take away from my article: most programmers aren’t thinking about this complexity. Many choose tools because it’s easier for them, or because it’s what they know, or because developer time is more expensive than the user’s CPU cycles or battery life and the engineers aren’t signing the checks. I hoped that many people would be surprised at just how much work their average programming language could end up doing even when given simple tasks.

The point was not that your programming language is wrong, or that being higher up on the table is better, or that programming languages should be blindly optimizing these numbers. The point is, if these numbers surprised you, then you should find out why! I’m a systems programmer — I want you to be interested in your systems! And if this surprises you, I wonder what else might…

I know that article didn’t do a good job of explaining any of this. I’m sorry.

Now to address more specific comments:

What the fuck is a syscall?

This question is more common with users of the languages which make more of them, ironically. A syscall is when your program asks the kernel to do something for it. This causes a transition from user space to kernel space. This transition is one of the more expensive things your programs can do, but a program that doesn’t make any syscalls is not a useful program: syscalls are necessary to do any kind of I/O (input or output). Wikipedia page.

On Linux, you can use the strace tool to analyze the syscalls your programs are making, which is how I obtained the numbers in the original article.

This “benchmark” is biased against JIT’d and interpreted languages.

Yes, it is. It is true that many programming environments have to factor in a “warm up” time. This argument on its face-value is apparently validated by the cargo-culted (and often correct) wisdom that benchmarks should be conducted with timers in-situ, post warm-up period, with the measured task being repeated many times so that trends become more obvious.2 It’s precisely these details, which the conventional benchmarking wisdom aims to obscure, that I’m trying to cast a light on. While a benchmark which shows how quickly a bunch of programming languages can print “hello world” a million times3 might be interesting, it’s not what I’m going for here.

Rust is doing important things with those syscalls.

My opinion on this is mixed: yes, stack guards are useful. However, my “hello world” program has zero chance of causing a stack overflow. In theory, Rust should be able to reckon whether or not many programs are at risk of stack overflow. If not, it can ask the programmer to specify some bounds, or it can emit the stack guards only in those cases. The worst option is panicking, and I’m surprised that Crustaceans feel like this is sufficient. Funny, given their obsession with “zero cost” abstractions, that a nonzero-cost abstraction would be so fiercely defended. They’re already used to overlong compile times, adding more analysis probably won’t be noticed ;)

Go is doing important things with those syscalls.

On this I wholly disagree. I hate the Go runtime, it’s the worst thing about an otherwise great language. Go programs are almost impossible to debug for having to sift through mountains of unrelated bullshit the program is doing, all to support a concurrency/parallelism model that I also strongly dislike. There are some bad design decisions in Golang and stracing the average Go program brings a lot of them to light. Illumos has many of its own problems, but this article about porting Go to it covers a number of related problems.

Wow, Zig is competitive with assembly?

Yeah, I totally had the same reaction. I’m interested to see how it measures up under more typical workloads. People keep asking me what I think about Zig in general, and I think it has potential, but I also have a lot of complaints. It’s not likely to replace C for me, but it might have a place somewhere in my stack.

-

For efficient display of unskippable 30 second video ads, of course. ↩︎

-

This approach is the most “fair” for comparison’s sake, but it also often obscures a lot of the practical value of the benchmark in the first place. For example, how often is the branch predictor and L1 cache going to be warmed up in favor of the measured code in practice? ↩︎

-

All of them being handily beaten by

/bin/yes "hello world"↩︎