This is the third in a series of articles on the subject of writing a Wayland compositor from scratch using wlroots. Check out the first article if you haven’t already. We left off with a Wayland server which accepts client connections and exposes a handful of globals, but does not do anything particularly interesting yet. Our goal today is to do something interesting - render a window!

The commit that this article dissects is 342b7b6.

The first thing we have to do in order to render windows is establish the

compositor. The wl_compositor global is used by clients to allocate

wl_surfaces, to which they attach wl_buffers. These surfaces are just a

generic mechanism for sharing buffers of pixels with compositors, and don’t

carry an implicit role, such as “application window” or “panel”.

wlroots provides an implementation of wl_compositor. Let’s set aside a

reference for it:

struct mcw_server {

struct wl_display *wl_display;

struct wl_event_loop *wl_event_loop;

struct wlr_backend *backend;

+ struct wlr_compositor *compositor;

struct wl_listener new_output;

Then rig it up:

wlr_primary_selection_device_manager_create(server.wl_display);

wlr_idle_create(server.wl_display);

+ server.compositor = wlr_compositor_create(server.wl_display,

+ wlr_backend_get_renderer(server.backend));

+

wl_display_run(server.wl_display);

wl_display_destroy(server.wl_display);

If we run mcwayface now and check out the globals with weston-info, we’ll see

a wl_compositor and wl_subcompositor have appeared:

interface: 'wl_compositor', version: 4, name: 8

interface: 'wl_subcompositor', version: 1, name: 9

You get a wl_subcompositor for free with the wlroots wl_compositor implementation. We’ll discuss subcompositors in a later article. Speaking of things we’ll discuss in another article, add this too:

wlr_primary_selection_device_manager_create(server.wl_display);

wlr_idle_create(server.wl_display);

server.compositor = wlr_compositor_create(server.wl_display,

wlr_backend_get_renderer(server.backend));

+ wlr_xdg_shell_v6_create(server.wl_display);

+

wl_display_run(server.wl_display);

wl_display_destroy(server.wl_display);

return 0;

Remember that I said earlier that surfaces are just globs of pixels with no role? xdg_shell is something that can give surfaces a role. We’ll talk about it more in the next article. After adding this, many clients will be able to connect to your compositor and spawn a window. However, without adding anything else, these windows will never be shown on-screen. You have to render them!

Something that distinguishes wlroots from libraries like wlc and libweston is that wlroots does not do any rendering for you. This gives you a lot of flexibility to render surfaces any way you like. The clients just gave you a pile of pixels, what you do with them is up to you - maybe you’re making a desktop compositor, or maybe you want to draw them on an Android-style app switcher, or perhaps your compositor arranges windows in VR - all of this is possible with wlroots.

Things are about to get complicated, so let’s start with the easy part: in

the output_frame handler, we have to get a reference to every wlr_surface we

want to render. So let’s iterate over every surface our wlr_compositor is

keeping track of:

wlr_renderer_begin(renderer, wlr_output);

+ struct wl_resource *_surface;

+ wl_resource_for_each(_surface, &server->compositor->surfaces) {

+ struct wlr_surface *surface = wlr_surface_from_resource(_surface);

+ if (!wlr_surface_has_buffer(surface)) {

+ continue;

+ }

+ // TODO: Render this surface

+ }

wlr_output_swap_buffers(wlr_output, NULL, NULL);

The wlr_compositor struct has a member named surfaces, which is a list of

wl_resources. A helper method is provided to produce a wlr_surface from its

corresponding wl_resource. The wlr_surface_has_buffer call is just to make

sure that the client has actually given us pixels to display on this surface.

wlroots might make you do the rendering yourself, but some tools are provided to help you write compositors with simple rendering requirements: wlr_renderer. We’ve already touched on this a little bit, but now we’re going to use it for real. A little bit of OpenGL knowledge is required here. If you’re a complete novice with OpenGL1, I can recommend this tutorial to help you out. Since you’re in a hurry, we’ll do a quick crash course on the concepts necessary to utilize wlr_renderer. If you get lost, just skip to the next diff and treat it as magic incantations that make your windows appear.

We have a pile of pixels, and we want to put it on the screen. We can do this with a shader. If you’re using wlr_renderer (and mcwayface will be), shaders are provided for you. To use our shaders, we feed them a texture (the pile of pixels) and a matrix. If we treat every pixel coordinate on our surface as a vector from (0, 0); top left, to (1, 1); bottom right, our goal is to produce a matrix that we can multiply a vector by to find the final coordinates on-screen for the pixel to be drawn to. We must project pixel coordinates from this 0-1 system to the coordinates of our desired rectangle on screen.

There’s gotcha here, however: the coordinates on-screen also go from 0 to 1,

instead of, for example, 0-1920 and 0-1080. To project coordinates like

“put my 640x480 window at coordinates 100,100” to screen coordinates, we use an

orthographic projection matrix. I know that sounds scary, but don’t worry -

wlroots does all of the work for you. Your wlr_output already has a suitable

matrix called transform_matrix, which incorporates into it the current

resolution, scale factor, and rotation of your screen.

Okay, hopefully you’re still with me. This sounds a bit complicated, but the

manifestation of all of this nonsense is fairly straightforward. wlroots

provides some tools to make it easy for you. First, we have to prepare a

wlr_box that represents (in output coordinates) where we want the surface to

show up.

struct wl_resource *_surface;

wl_resource_for_each(_surface, &server->compositor->surfaces) {

struct wlr_surface *surface = wlr_surface_from_resource(_surface);

if (!wlr_surface_has_buffer(surface)) {

continue;

}

- // TODO: Render this surface

+ struct wlr_box render_box = {

+ .x = 20, .y = 20,

+ .width = surface->current->width,

+ .height = surface->current->height

+ };

}

Now, here’s the great part: all of that fancy math I was just talking about can

be done with a single helper function provided by wlroots: wlr_matrix_project_box.

struct wl_resource *_surface;

wl_resource_for_each(_surface, &server->compositor->surfaces) {

struct wlr_surface *surface = wlr_surface_from_resource(_surface);

if (!wlr_surface_has_buffer(surface)) {

continue;

}

struct wlr_box render_box = {

.x = 20, .y = 20,

.width = surface->current->width,

.height = surface->current->height

};

+ float matrix[16];

+ wlr_matrix_project_box(&matrix, &render_box,

+ surface->current->transform,

+ 0, &wlr_output->transform_matrix);

}

This takes a reference to a float[16] to store the output matrix in, a box you

want to project, some other stuff that isn’t important right now, and the

projection you want to use - in this case, we just use the one provided by

wlr_output.

The reason we make you understand and perform these steps is because it’s entirely possible that you’ll want to do them differently in the future. This is only the simplest case, but remember that wlroots is designed for every case. Now that we’ve obtained this matrix, we can finally render the surface:

struct wl_resource *_surface;

wl_resource_for_each(_surface, &server->compositor->surfaces) {

struct wlr_surface *surface = wlr_surface_from_resource(_surface);

if (!wlr_surface_has_buffer(surface)) {

continue;

}

struct wlr_box render_box = {

.x = 20, .y = 20,

.width = surface->current->width,

.height = surface->current->height

};

float matrix[16];

wlr_matrix_project_box(&matrix, &render_box,

surface->current->transform,

0, &wlr_output->transform_matrix);

+ wlr_render_with_matrix(renderer, surface->texture, &matrix, 1.0f);

+ wlr_surface_send_frame_done(surface, &now);

}

We also throw in a wlr_surface_send_frame_done for good measure, which lets

the client know that we’re done with it so they can send another frame. We’re

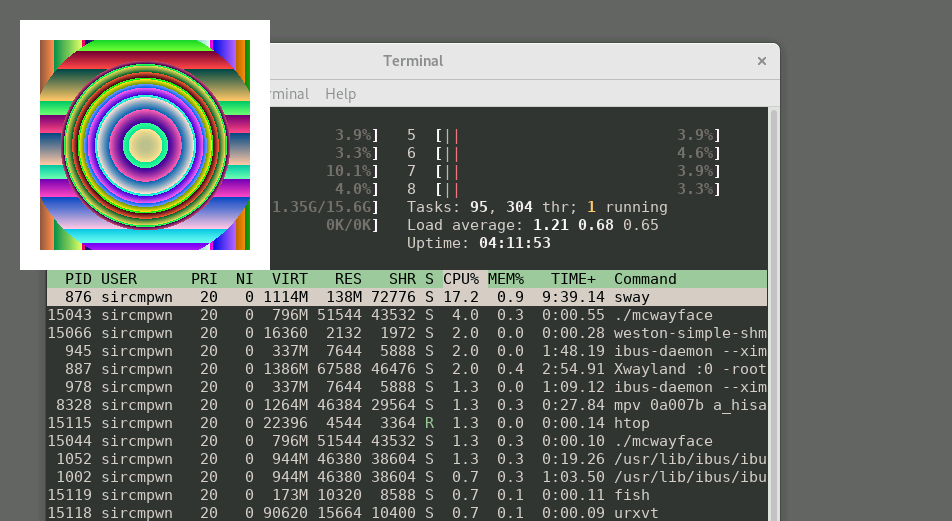

done! Run mcwayface now, then the following commands:

$ WAYLAND_DISPLAY=wayland-1 weston-simple-shm &

$ WAYLAND_DISPLAY=wayland-1 gnome-terminal -- htop

To see the following beautiful image:

Run any other clients you like - many of them will work!

We used a bit of a hack today by simply rendering all of the surfaces the

wl_compositor knew of. In practice, we’re going to need to extend our

xdg_shell support (and add some other shells, too) to do this properly. We’ll

cover this in the next article.

Before you go, a quick note: after this commit, I reorganized things a bit - we’re going to outgrow this single-file approach pretty quickly soon. Check out That commit here.

See you next time!

Previous — Part 2: Rigging up the server

-

If you’re not a novice, we’ll cover more complex rendering scenarios in the future. But the short of it is that you can implement your own

wlr_rendererthat wlr_compositor can use to bind textures to the GPU and then you can do whatever you want. ↩︎